“Why are my cells sticking to the vessel when I’m using microcarriers?”

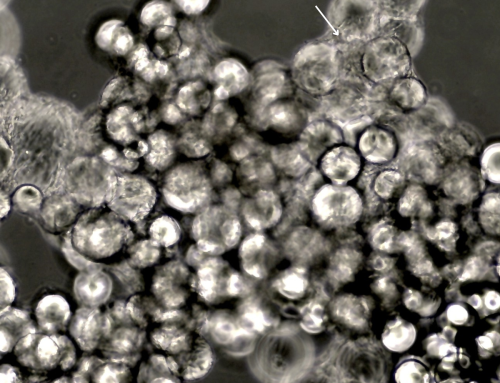

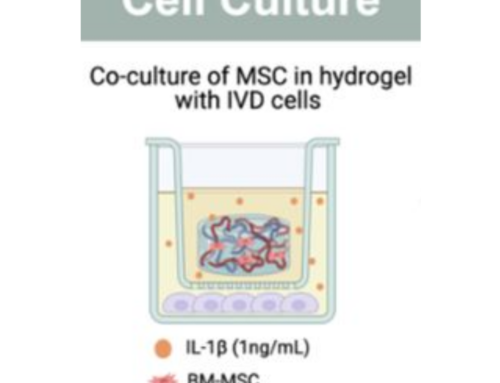

It’s one of the most common questions researchers ask when working with microcarrier-based cell culture, especially with highly adherent cells like mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).

Yet after 24 hours, cells are clearly attached to the vessel walls, flask bottom, or bioreactor internals.

The reality is simple: cells don’t know which surface you intended them to attach to.

What’s Really Going On?

During the first hours after seeding, cells will attach to any compatible surface they encounter. Microcarriers are just one option.

If vessel surfaces are adhesive, and most standard plastics and glass are, they compete directly with microcarriers for cell attachment. Once cells attach, that decision is usually permanent.

This is why unintended vessel attachment is so common, even in well-designed systems.

Why This Matters in Microcarrier-Based Culture

Microcarrier systems rely on controlled attachment.

When cells attach to non-microcarrier surfaces, it can lead to:

- Reduced effective microcarrier surface utilisation

- Uneven cell distribution

- Increased run-to-run variability

- Complications during scale-up

Importantly, this is not a microcarrier failure, it’s a surface-control issue.

How to Reduce Unwanted Cell Attachment

1. Remove Competing Surfaces Early

The most effective strategy is to eliminate adhesive vessel surfaces before cells are introduced.

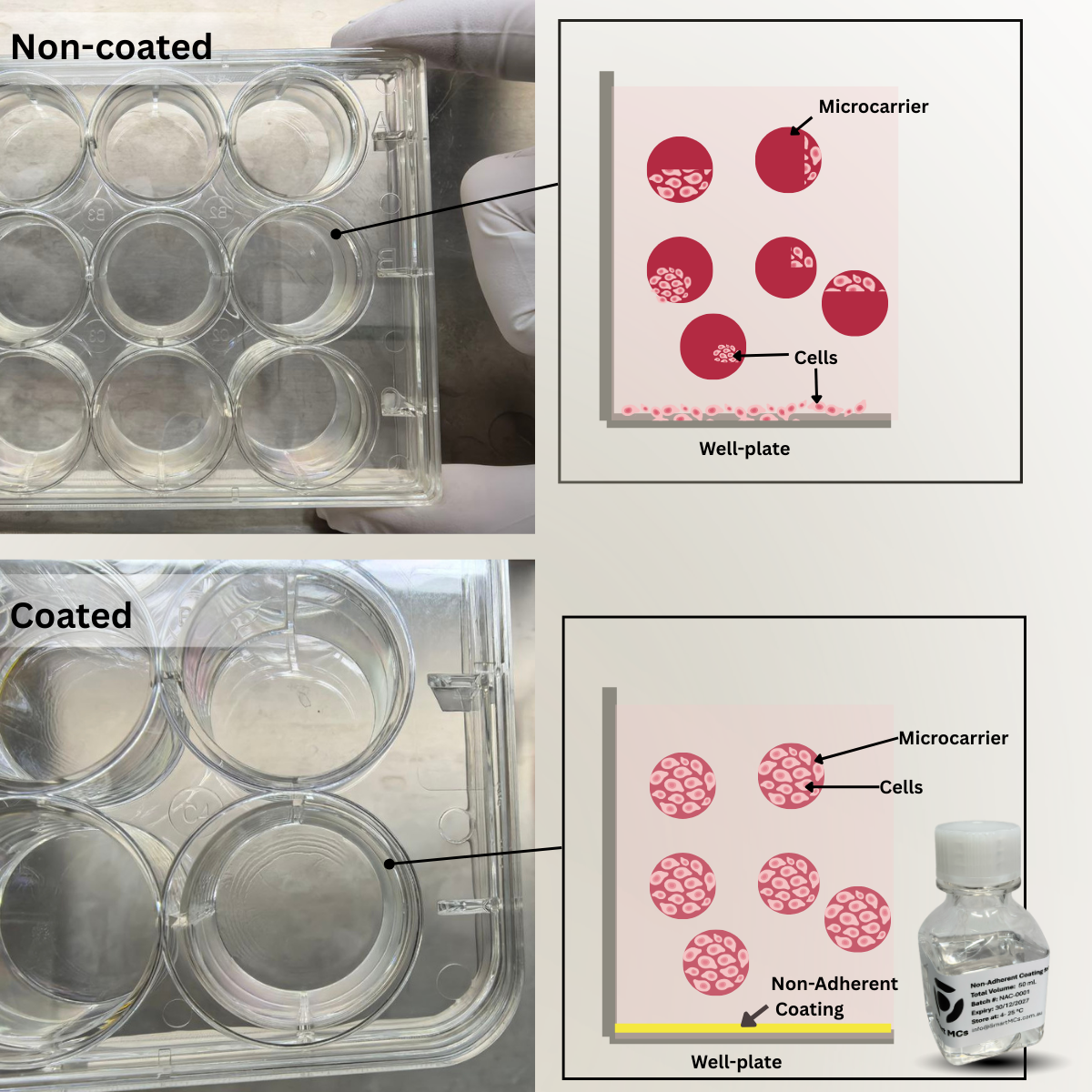

NAC (Non-Adherent Coating) from Smart MCs is designed to uniformly coat laboratory vessels, including well plates, flasks, bottles, and other culture surfaces, to significantly reduce unwanted cell attachment.

By modifying surface chemistry, the coating can:

- Reduce protein adsorption onto the vessel surface (proteins often enable cell attachment)

- Create a low-adhesion surface that cells cannot grip easily

- Minimise unwanted attachment to vessel walls and bottoms during early seeding

- Encourage cells to attach to microcarriers rather than competing vessel surfaces

- Improve reproducibility in microcarrier-based cultures by reducing variability from vessel attachment

Why does this work? Cells tend to attach to surfaces that allow proteins from the culture medium to adsorb and form “adhesive cues,” which is influenced by surface charge and wettability (hydrophilicity). Many standard plastics and glass surfaces quickly become protein-coated after media addition, making them cell-adhesive. A non-adherent coating shifts the vessel surface toward a more hydrophilic, low-adhesion state, reducing stable attachment and helping cells preferentially attach to microcarriers instead.

Some labs also use agarose-coated vessels as a low-attachment option, but coatings can vary in consistency depending on handling. A ready-to-use coating is usually easier when you want repeatable results.

2. Pay Attention to the Seeding Phase

The first 24 hours post-inoculation largely determine where cells end up.

Best practice includes:

- Fully hydrating and evenly suspending microcarriers

- Establishing mixing before cell addition

- Avoiding prolonged static conditions during early attachment

Early decisions have long-term consequences.

3. Maintain Uniform Cell Distribution

If the culture is not mixing well, cells and microcarriers can sink and collect at the bottom or in “quiet areas” of the vessel. When cells sit on the plastic or glass for too long, they can attach there by accident instead of attaching to the microcarriers.

So the goal during seeding is simple: keep cells and microcarriers moving and evenly spread out, so cells meet microcarriers more often than they meet the vessel surface.

In practice, this means:

- Mixing enough to keep microcarriers evenly suspended (no clumps or dead zones)

- Choosing a seeding method that fits your system (static, intermittent mixing, or continuous stirring)

- Not leaving the culture fully still for too long if cells start settling to the bottom

Some sticky cells (like MSCs or fibroblasts) may still stick a little, even with a non-adherent coating. The goal is to reduce it as much as possible, so more cells end up on the microcarriers. This doesn’t necessarily mean higher agitation, it means keeping cells consistently exposed to microcarriers rather than vessel surfaces, especially during the early seeding phase.

Agitation strategy plays a central role in achieving uniform suspension and directing attachment toward microcarriers. For a more detailed discussion on selecting and optimising agitation parameters across different culture phases, see our guide on 5 Essential Tips for Optimising Agitation in Microcarrier Culture.

A Simple Rule of Thumb

If cells are attaching to the vessel, ask:

“Did the cells encounter the vessel surface before they encountered the microcarriers?”

If the answer is yes, If the answer is yes, focus on vessel preparation and early seeding conditions, because once cells stick to the vessel, it’s much harder to move them back onto microcarriers.

Key Takeaways

- Cells attach to surfaces they encounter early

- Vessel surfaces compete with microcarriers for attachment

- Unintended attachment is predictable and preventable

- Non-adherent coatings remove ambiguity from the system

Interested in Dissolvable Microcarriers?

For teams looking to streamline attachment and downstream processing, dissolvable microcarriers can be a useful option to explore.

These platforms are designed for applications where easy carrier removal, reliable cell attachment, and simplified downstream recovery are important.

Final Thought

Microcarrier culture works best when cell behaviour is guided, not assumed.

By controlling surface interactions from the outset, especially through the use of non-adherent vessel coatings, researchers can achieve more consistent, scalable, and reproducible outcomes.